Common Sense, Then and Now: Why Thomas Paine Still Matters

By: Jessie Simmons

Category: Civic Foundations & Democratic Governance

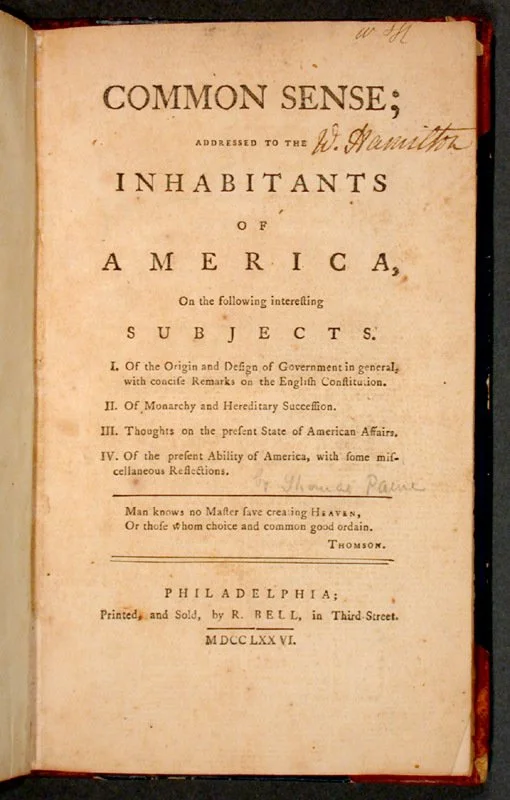

January 10 is a quiet anniversary in American history, but it should not be. On this day in 1776, Thomas Paine published Common Sense, a short pamphlet that helped change the course of a continent.

It was not written for scholars or political elites. It was written for regular people. Farmers. Tradesmen. Shopkeepers. Anyone willing to read, argue, and decide for themselves whether the world they lived in actually made sense.

At the time, many colonists still hoped for reconciliation with Britain. Paine challenged that instinct head-on. He argued that monarchy was not only unjust, but irrational. That hereditary power defied reason. That an island ruling a continent was absurd. More importantly, he insisted that political legitimacy comes from the people themselves, not from tradition, title, or force.

What made Common Sense revolutionary was not just its conclusions, but its approach. Paine stripped politics of ceremony and intimidation. He wrote plainly, emotionally, and directly. He treated ordinary citizens as capable of understanding complex ideas and making moral judgments about power. That assumption alone was radical.

The impact was immediate. The pamphlet spread rapidly throughout the colonies, read aloud in taverns and meeting halls, debated in homes and streets. In a population of only a few million, hundreds of thousands of copies circulated. It did not merely reflect revolutionary sentiment. It accelerated it, helping shift the colonies from reluctant resistance toward full independence and ultimately the American Revolution.

Nearly 250 years later, it is fair to ask whether Common Sense still speaks to us.

Our world is undeniably more complex than Paine’s. We live within sprawling institutions, permanent bureaucracies, global systems, and technologies that shape daily life in invisible ways. Politics often feels distant, technical, and inaccessible. Many people respond by disengaging, or by retreating into tribal loyalty instead of civic responsibility.

Yet the core warning Paine offered feels remarkably current. He cautioned against mistaking longevity for legitimacy. Against accepting systems simply because they exist. Against surrendering judgment to authority out of habit or fear. He believed that reason should always be allowed to question power, no matter how established that power may be.

Today’s national divisions are often described as ideological, but they run deeper than policy disputes. They are divisions over trust, over shared reality, and over whether disagreement is something to be worked through or something to be crushed. Too often, politics has become a contest of identities rather than a process of persuasion.

Common Sense does not give us modern policy answers. That is not its value. Its value lies in its posture toward self-government. Paine assumed that citizens could argue in good faith, could change their minds, and could take responsibility for the direction of their society. He rejected the idea that people were too ignorant or too divided to govern themselves.

A return to that mindset would not magically heal our divisions. But it could change how we engage with them. Debate grounded in reason is healthier than conflict driven by contempt. Skepticism toward concentrated power is healthier than blind loyalty. Citizenship is healthier than spectatorship.

On this anniversary, the enduring lesson of Common Sense is not about 18th-century grievances. It is about civic courage. About refusing to outsource moral judgment. About believing that people, when spoken to honestly and respectfully, are capable of thinking clearly.

That idea built a nation once.

It may be worth remembering again.