The Rising Cost of Keeping the Lights On in Washington: How rate cases and climate mandates are affecting everyday households

By Jessie Simmons

Category: Energy and Affordability

Puget Sound Energy has filed notice that another General Rate Case is coming. In early January, the utility submitted Notices of Intent to file new electric and natural gas rate cases with the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission. The electric filing is listed under UE-260005. The gas filing appears under UG-260006. On paper, this looks procedural. Another filing. Another docket. Another step in a long regulatory process. For households across Washington, it does not feel procedural at all. It feels like the next shoe dropping on bills that have already changed dramatically since 2020. To understand why, you have to look beyond bill summaries and into the tariffs and Commission orders that quietly determine what people pay.

For residential electric customers, the clearest reference point is Schedule 7, the standard residential rate used by Puget Sound Energy. Schedule 7 sets the base price of electricity in cents per kilowatt hour, before riders, trackers, and taxes are layered on. In mid-2020, the structure was relatively stable. The first 600 kilowatt hours per month were priced at about 10.6 cents per kilowatt hour. Usage above 600 kilowatt hours was cheaper, about 8.7 cents per kilowatt hour. By early 2026, that structure has fundamentally changed. The first 600 kilowatt hours are priced at more than 14.1 cents per kilowatt hour. Usage above 600 kilowatt hours now exceeds 16.1 cents per kilowatt hour. That shift is visible directly in the Schedule 7 tariff sheets on file with the Commission. Measured strictly on the base energy charge, Tier 1 usage has increased about 33 percent since 2020. Tier 2 usage has increased more than 80 percent. These are not total bills. This is the foundation everything else is built on. When you translate that into real household dollars, the impact becomes obvious.

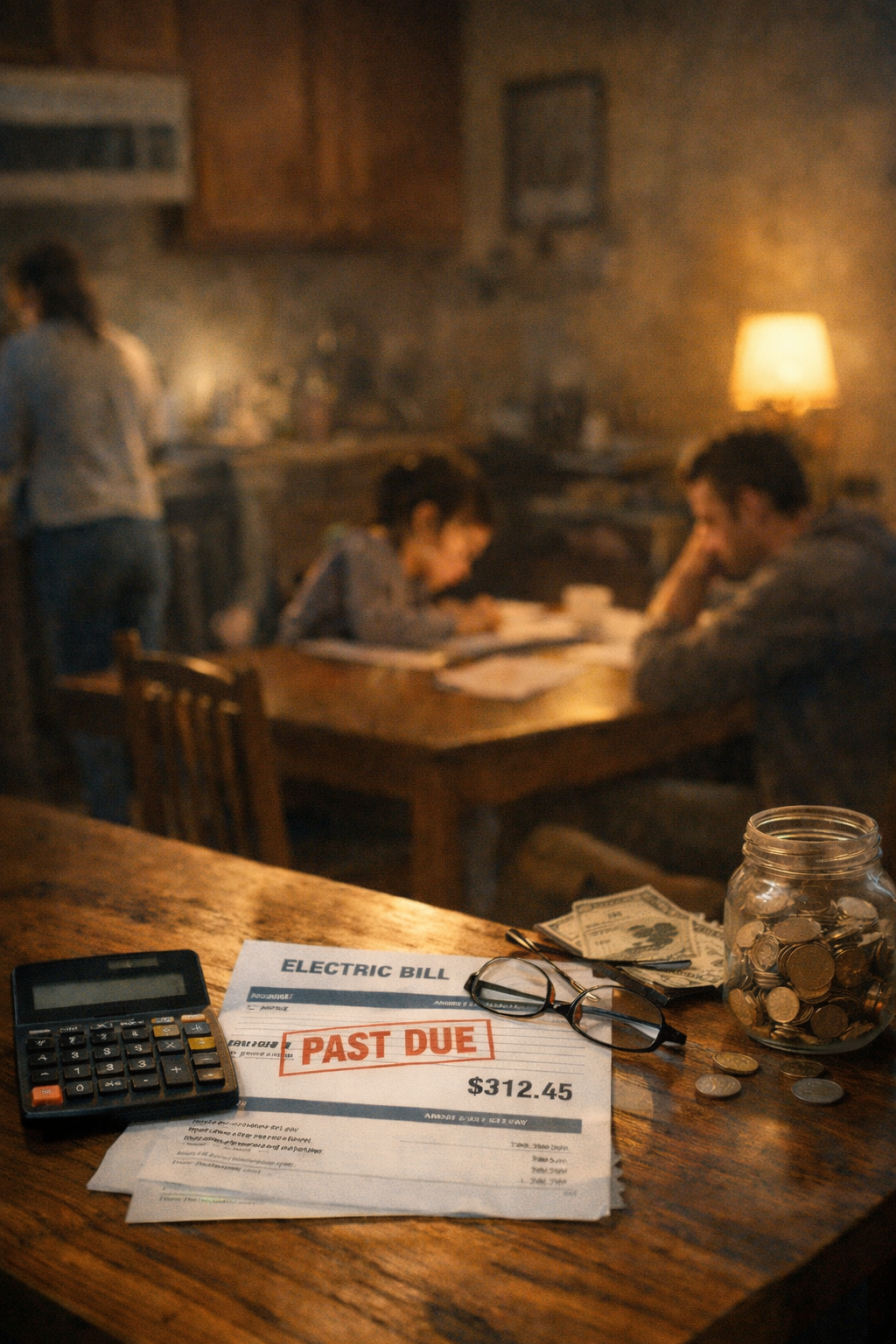

A household using around 1,100 kilowatt hours per month, which is common for families in older homes or with electric heat, typically paid around $190 to $210 per month for electricity in 2020, depending on season and adjustments. Today, that same household is commonly paying $300 to $330 per month on a budget plan. That is an increase of roughly $110 to $130 per month, or $1,300 to $1,500 per year, for the same electricity use. Those costs are already baked in. They reflect years of approved increases, including the multi-year rate plan that took effect in January 2025 and January 2026, along with power cost updates and other adjustments. They do not include what may come next from the newly noticed General Rate Case. This is why the word “incremental” rings hollow for households. From a regulatory standpoint, each filing is incremental. From a household standpoint, there is no reset. There is only a bill that keeps rising and never comes back down.

The reason this feels cumulative is structural. When a General Rate Case is approved, the higher cost becomes the new baseline. Future increases stack on top of that baseline. Investments made today remain in rates for decades. There is no mechanism that naturally pushes bills back down. This is where climate policy enters the picture, and it matters how this is described. The Clean Energy Transformation Act and the Climate Commitment Act did not single-handedly cause Washington’s electric bills to rise. But they changed the direction and pace of cost growth.

CETA requires utilities to transition their power portfolios on an accelerated timeline. That means long-term contracts, new generation, grid upgrades, storage, and system integration costs that are recovered through rates.

The CCA adds a carbon compliance obligation. Utilities receive some allowances at no cost, but not enough to fully cover their exposure. Additional allowances must be purchased, and those costs flow directly into power costs recovered from customers.

This is not an interpretation. In recent approvals, the Washington Utilities and Transportation Commission has explicitly stated that electric rate increases reflect power costs associated with CCA compliance, accelerated clean energy investments under CETA, and the reliability upgrades required to support that transition. Those statements appear in Commission materials approving rate changes effective January 1, 2026, alongside approval of expanded bill discount programs.

Taken together, the public record supports a conservative conclusion: 40 to 60 percent of the electric bill increase households have experienced since 2020 is directly tied to climate policy implementation and clean energy mandates. Applied to a realistic household bill, that means $45 to $70 per month, or $540 to $840 per year, is now embedded in electric bills as a result of climate policy choices. These are recurring costs. They are not temporary surcharges. And they arrive during a period of economic stress when housing, insurance, food, and childcare costs are already straining family budgets. This is where energy choice matters.

A transition to cleaner energy does not require narrowing the system to fewer resources all at once. Maintaining a diversity of energy sources supports grid reliability, dampens price volatility, and gives households time to adapt. When diversity is reduced too quickly, costs rise faster and flexibility disappears. Being pro-clean energy does not require being indifferent to household affordability. It requires acknowledging that how the transition is financed matters just as much as the goal itself.

The new General Rate Case notice matters because it signals another baseline reset. For a household already paying $300 per month, even a 6 to 10 percent increase adds $18 to $30 per month, or $200 to $400 per year, on top of what has already happened since 2020. Based on recent Commission findings, a meaningful share of that increase is likely to be tied again to climate compliance and clean energy requirements. From a docket perspective, this may look incremental. From a household perspective, it feels relentless.

Washington’s energy transition will succeed only if it maintains reliability, preserves energy choice, and spreads costs in a way families can actually absorb. The tariffs show how far the system has already moved. The next General Rate Case will determine how much farther it goes, and who pays for it.